Electric 2-Wheelers Adoption Rate Modelling via System Dynamics

"What government policy scenario is best for increasing electrification rate and reducing carbon emissions in Indonesia's motorcycle system?"

Abstract

Indonesia runs on motorcycles. Over 100 million of them—almost all burning gasoline, collectively emitting 50 megatons of carbon per year. The government wants to electrify. But how? Which levers actually work? And what happens when you pull them?

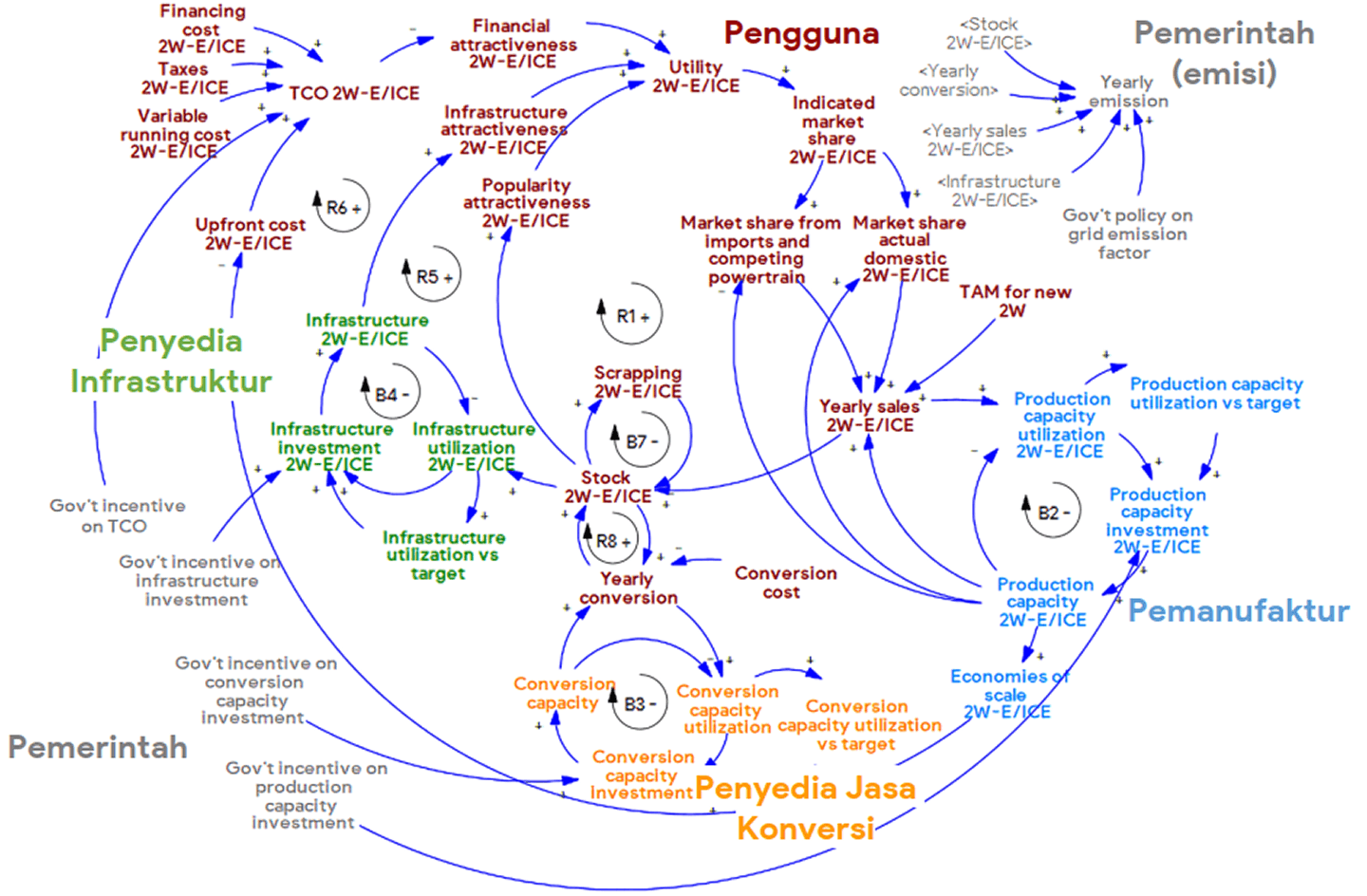

This research builds a system dynamics model of Indonesia's motorcycle ecosystem from 2023 to 2045—simulating five interacting agents: users choosing between electric and ICE, manufacturers scaling production, conversion workshops retrofitting old bikes, infrastructure providers building battery swap and gas stations, and a government trying to steer it all through incentives and disincentives.

The model tests 726 policy scenarios across three lever groups: industry focus (subsidies for production, TCO incentives), infrastructure focus (swap stations vs gas stations), and grid decarbonization (four trajectories from status quo to most ambitious). User decisions are modeled through utility functions shaped by financial attractiveness, popularity, and infrastructure availability—then converted to market share via multinomial logit.

The results are sobering. The best-performing scenarios (669, 130, and 9) can push electric motorcycle stock to ~58 million units by 2045—but even combined with the most aggressive grid decarbonization (LCCP), none of them reduce annual emissions below 2023 levels. Emissions peak around 2039, then decline—but not fast enough. The dominant emission source isn't manufacturing or infrastructure; it's usage. Millions of vehicles running on a still-dirty grid.

Other findings: the system exhibits bullwhip dynamics in production capacity. Policy effectiveness is regime-dependent—supply-side incentives only work when production is the bottleneck; demand-side incentives only matter when demand is the constraint. Disincentivizing ICE production doesn't help because ICE is perpetually demand-constrained. And crucially, Indonesia would need to decarbonize its electrical grid more aggressively than currently planned just to hold emissions steady.

The model doesn't pretend to predict the future. But it makes assumptions explicit, trade-offs visible, and debates possible. The code runs. The scenarios are reproducible. The implications are for policymakers to decide.